At some point in one’s language learning, it seems as if there is nothing left to learn, yet fluency still has not been attained. However, never forget that there is always more to a language than vocabulary and grammar. There is the way that it is used everyday in that descriptive, poetic, idiomatic way that just never seems to be taught in school. I have studied French for thirty years. Granted, not all of that time has been spent in school. Many of those years were outside the classroom, in my many travels to France and Francophone countries, through my many subscriptions to magazines and newspapers, in all of my reading and through all of the movies and news programs I have enjoyed since finishing school. Yet there were times when I still felt my French was grammatically hyper-correct, that kind of “book French” for which my friends mocked me, yet not colloquial. I had never mastered the idiom.

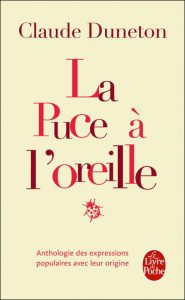

Thanks to the Alliance Francaise, I discovered Claude Duneton’s La puce à l’oreille: anthologie des expressions populaires avec leur origine. Perfect! It was just what I needed. I highly recommend this for the advanced French language student who is looking for a deeper understanding of the language and where certain expressions come from and why the French express things in certain ways.

This is not your typical book of idioms. A typical book of idioms will give a student a list of idioms and the meanings as best translated in English. On occasion, however, after discussion with a native speaker, I have determined some of the “translations” in such books to be inaccurate, not quite grasping the original meaning, or just not quite the equivalent. Understandably, it is very difficult to translate some popular expressions. Yet a simple “dictionary” of idioms does not make for easy memorization, either. This book by Duneton reads like stories. They are memorable stories, about the history of certain expressions, tracing their origins back to old French words with the occasional or eventual change of meaning that sometimes takes place. It was so memorable that maybe a few months later, at a film showing at the Alliance Francaise, I heard one of the characters using several of these expressions in the movie, and I did not need to make use of the subtitles to catch the meaning. That might not have happened had I not just recently read this book.

A fairly common idiom that a student might even learn at school would be something like tomber en panne. We learn this to mean “break down”, but what is a panne and why does it have to fall? We will learn from Duneton that this is a nautical term and the fascinating story of what panne means. Some of these expressions are very old and rarely used, but not too many. I regularly come across some of these in books, even in ones that I have read even recently, like tenir le haut du pavé or se mettre sur son trente et un. You will also learn the origin of an expression which is very common even in English, le cordon bleu. Putting the cart before the horse (which in French comes to: mettre la charrue avant les boeufs) may have its origins in old French labor idioms. These are clearly explained in this book, and now I know them when I see them. It makes my reading that much more enjoyable.

Another unexpected outcome and welcome realization is discovering why we say in French grand-mère without the extra e on grand. Mère is feminine, why is grand not in the feminine form? Grand at the time was invariable and took masculine and feminine nouns. There are other gems that we will learn here, like why ouvrier means worker, but ouvert means open, literally open for work. Yet, there are words for work and those are now travail and travailler which used to mean “torture”. I find this fascinating!

I cannot sufficiently sing the praises of this work. You will simply have to discover it for yourselves. It is most definitely for the very advanced French reader, and you will certainly need a very good dictionary if you want to search for some of the words used that are simply not so common in French today. Despite the difficulty of the text itself and the sources cited in old French, I do highly recommend it for anyone who wants a more fuller experience and glimpse into the highly colorful colloquial French. We never stop learning a language. It is a life-long experience. I find it very exciting to learn new words or phrases, and common expressions, especially the colorful ones! Vive le français!