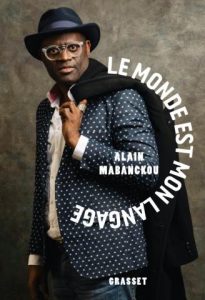

The newly published book by Alain Mabanckou, Le Monde est Mon Langage, is a tour of the French-speaking world in a series of essays. His travels take him all throughout the world meeting, occasionally by chance, French speakers and writers in the most unlikely of places, discussing literature, politics, francophonie, and the history of French literature as it appears in various places all over the world.

In his captivating introduction he explains how this autobiographie capricieuse came about. He himself became a writer, not because he had to leave his native country, but because writing helped him to look at his world differently. Having lived on three continents, he says that he discovered this world through this point-of-view français. This is a book about the relationships that he has created with the people that he has met in his travels, calling them “ambassadors”, many of whom write in a language other than their native language, that same language that Mabanckou has adopted for his writing. French does not belong only to the French, but is spoken the world over. Many of the writers he will meet and write about are multi-national, multi-lingual and write in search of identity or on the theme of exile.

Chapter one begins in Paris where he meets the writer Le Clésio for a conference and remembers his relationship with him over the years. Le Clésio, whose mother is from France, father from Mauritius but Breton by birth, now lives in New Mexico. Their philosophical discussions on writing and language are fascinating and inspiring. These discussions set the tone for the book, and I especially enjoyed envisioning these two great men of literature strolling through the gardens of Paris while in deep discussion. As the first and longest chapter, it seems to me that this one was indeed the most important. His next stop is to my beloved New Orleans and a meeting with a man who claims to have roots with the Haitian hero Toussaint Louverture!

One of the many reasons why I find this book fascinating and captivating is, as I have said above, when he and his friends discuss topics such as the purpose of language, art, writing, poetry, whether poetry is dead, how poets are the guardians of the language and how a single language cannot define the world. These philosophical discussions are for me so thought-provoking and precious. I read slowly and carefully, taking notes and occasionally putting it down just to contemplate.

Quite often the chapters in the book read like a biography with references to the most significant works produced by these writers and the impact their work has had on the literature of the region and the Francophone world. Some people may see them as dry, but to me they are always eye-opening, create great discussions and sometimes have sparked my interest in a certain writer or his work. There are many chapters in which discussions will range from créolité, antillanité, the créolisation of Europe, to identity and exile, in the works of such authors as Edouard Glissant, Camara Laye, and Gary Victor, just to name a few.

Another of my favorite chapters is the one on Montreal with Dany Laferrière and his friend Rodney Saint-Éloi. It is partially a story, partially an interview. I have appreciated Dany’s humor and use of metaphor ever since I first discovered his work. Even in this short chapter, his charm and humor come through. Mabanckou, a long-time friend of Dany’s, clearly knows how to capture his essence.

It is clear through his writing that the French language is precious to him, and that writing this book is like a love letter to les lettres françaises, French literature, all of it from everywhere in the world. For someone whose exposure to French literature outside of France is limited, this book is a great starting point. For the great bibliophile, this is also an important work to add to your shelves. Mabanckou’s defense of poetry, his pure belief in the importance of literature to move and inspire people will resonate with those passionate about language, as it has with me.

I have used it with students as a book club selection, with chapter by chapter discussion questions.

***Book available as a French Book Club Course, See my Services page***